If you didn’t play console RPGs until Pokemon and Final Fantasy VII, you were not alone. While console roleplaying games were wildly successful in Japan, whether it was the younger gaming demographic, the lack of appetite for anime, or something else, console RPGs were a niche genre in North America until the mid-90s.

The minute install base of console RPGs was not for lack of trying. Enix and Nintendo invested heavily in the localization and marketing of Dragon Quest in North America, yet despite the careful faux Elizabethan text, full color map and walkthrough, market-tailored new artwork, and ads in magazines, Dragon Warrior ended up being more successful selling Nintendo Power subscriptions (with which excess copies were given away for free) than it was in selling itself. Final Fantasy on NES received a similar marketing blitz, taking the cover of Nintendo Power despite being a genre console gamers had yet to latch onto, despite being an unknown series, and despite being 3 years old.

Dragon Warrior and Final Fantasy were not unsuccessful in North America, but they were also shadows of what they had been in Japan. In North America, we ended up seeing only half of the Final Fantasy series (mis-numbered at that) and never received localizations of the 16-bit Dragon Quest titles. We missed out on numerous important titles during this era, including all of the Romancing SaGa games, Live-a-Live, Shin Megami Tensei, and many, many more.

But somehow, we got one of the most bizarrely designed and esoteric games in this genre: we got SaGa.

Final Fantasy in More than Name

Given the collaborative, business-driven, global nature of games, I don’t really like applying auteur theory to them, but in the case of SaGa it is more than justified.

You cannot dive deep into the word of SaGa without hearing the name Akitoshi Kawazu. He is one of the only remaining vanguard of Square from the 80s still working at SquareEnix, and throughout his storied career, he’s been quite forthcoming with interviews, detailing his early history at Square and the formulation of what became the SaGa series.

Kawazu was always a great lover of board games, though his interest in them was nurtured by befriending another student who imported them frequently from North America. The experience of playing an English board game must be very different for a Japanese player. As all board game enthusiasts know, the best way to learn a game is to figure it out by playing it. As issues come up during those rough initial playthroughs, the manual should be used to elucidate the more nuanced rules. To a Japanese player, this journey is going to be more cryptic, slower, and more opaque as the game’s inner mechanics could be buried behind blocks of English text. Having played a few Avalon Hill games from this era, I cannot fathom how confusing it would be to play such a game without my native language.

In addition to board games, Kawazu was also a fan of early computer roleplaying games like Ultima and Wizardry. These games too are cryptic and punishing, even beyond their language barrier. Ultima IV, for example, has many systems in place that affect how the story can be progressed in non-transparent ways. Wizardry also has many punishing statistics like losing stats at level up and permanent death built around a system to discourage save scumming.

At Square, Kawazu worked as the battle scenario for the first Final Fantasy, developing many of the mechanics that would become a key part to both that series and to SaGa. While Dragon Quest made RPGs accessible with distinct Toriyama artwork and controls designed with the Famicom in mind, Hironobu Sakaguchi and the team at Square wanted to make something closer to western RPGs that were quite popular on Japanese computer systems but did not have a good analogue on the Famicom yet.

The battle system Kawazu designed is very much inspired by western RPGs, both video games and table top. From creating characters at the outset before even starting the game, to the use of D&D-style elemental attributes, to the bestiary that borrows so much from the D&D Monster Manual that it would likely provoke litigation if done today to the cryptic way many items have secondary uses that are never explained, Final Fantasy takes many elements from western roleplaying traditions and wraps them in a nice Japanese package.

For the sequel, Kawazu was elevated to the main scenario designer. Final Fantasy II tried an idea closer to Ultima IV than D&D--building a character through nurturing rather than raw power. While characters in FFII are named and have (for the time) personalities, they are also class-less and can pursue any skills or abilities through repeated use. You can become the greatest toad spell specialist the world has ever seen, if you want. It’s a novel system that obeys unintuitive rules with unintended consequences, such as attacking your own party to increase HP.

While FFII is the odd ball in the series now, to say it was odd from the beginning would be anachronistic. FFII actually outsold the first game in Japan by about 200,000 and was quite a success for Square, despite not being officially localized for the lucrative North American market. Given different circumstances--if Kawazu worked directly on Final Fantasy III--the first Final Fantasy might have been the odd one instead.

But the Gameboy was a runaway success; a game system that appealed to commuter-heavy Japanese businessmen and children alike. It was a popular platform without any RPGs too. Kawazu’s success with FFII (which was Square’s most successful game in their native Japanese market at that time) proved that he had the design understanding for this task.

For completely market-driven reasons, SaGa and Seiken Densetsu were re-branded as Final Fantasy Legend and Final Fantasy Adventure respectively for their western releases, but to say they are completely un-related would be wrong. Final Fantasy Adventure’s Japanese name--Seiken Densetsu: Final Fantasy Gaiden--explicitly indicates that it is a sidestory in the series, while Final Fantasy Legend continues many of these themes and ideas roughly developed in Final Fantasy II. Given different circumstances, SaGa could have ended up on consoles as Final Fantasy III.

Makai Toushi: Final Fantasy Gaiden

In 1989 there was no such thing as a portable RPG. Every iteration of an RPG that had ever been created on any platform--be it on computer, table top, or console--was a time consuming affair. From setup to lengthy dungeon expeditions, much of the challenge and enjoyment in roleplaying games came from the tactical considerations of balancing risk and endurance over rewards and progress. Many roleplaying games also prided themselves on artwork, such as the colorful masterpieces in Dragon Quest and the massive boss monsters in Final Fantasy.

A portable RPG needed to be designed very differently. The player needed to be able to stop and resume at a moment’s notice, such as when a commuter’s train arrived at a station, therefore the challenge could not simply be an endurance marathon. Likewise, scenarios needed to be small and digestible over brief sessions, fast enough so that playing for a few minutes did not feel like a waste of time.

SaGa did this in a few ways. First, it allowed the game to be saved anywhere at any time, all but eliminating session duration issues. The battle speed is significantly faster than console RPGs of the era, allowing the player to hold down the A button to blaze through battle text (but release it to slow down if something important happens). Unintunitively the encounter rate is also higher than what as seen in Square’s Final Fantasy series, a decision that Kawazu explained as wanting to make the game interesting if it was played for a brief period, so that even if the player had 5 minutes, they would be guaranteed to go through a few battles. Finally, enemies appear in Wizardry-style groups, where a single enemy image represents a group of foes. All of these decisions make SaGa significantly more playable on Gameboy than a portable version of the Famicom Final Fantasy would have been.

It wasn’t just technical decisions that makes SaGa suited for handheld play. It’s story is a collection of loosely connected episodic stories. The player is in a world where there is a mysterious tower reaching into the heavens. This tower is both a central dungeon as well as the entrance to other worlds with their own self-contained stories. Each story has its own themes, gimmicks, and boss. One world is covered by oceans and transverse by a floating island; another is a post-apocalyptic wasteland ravaged by an unbeatable monster. Beating the boss of a world allows the player to climb higher in the central tower until they reach the time. This works great for a portable experience since immediate goals are short and easily identified in smaller worlds, rather than trying to remember where to go next in a full world map found on Famicom RPGs.

SaGa's small, self-contained worlds are one of the clever ways the game makes it self accessible on a portable system

At around 12 hours, with just a few hours per world, SaGa is a fantastic portable length. Were this all that SaGa was about, it would have been a successful game based on these design decisions alone. But remember Final Fantasy II and remember Kawazu? Despite being the first RPG on the first viable portable platform, SaGa is anything but simple.

The Wisdom to Know the Difference

The SaGa series as a whole is often described as confusing, opaque, random, and lacking in player agency. While that’s true, it’s not without precedent.

If we go back to Kawazu’s early experiences with western board and roleplaying games, SaGa almost seems natural. Imagine picking up a complex modern board game like Agricola, Twilight Struggle, or Race for the Galaxy but rather than getting helpful documentation you got brief and cryptic rules in a foreign language. Figure it out by playing. That’s a close approximation to playing a SaGa game.

In board games too, a lack of agency is generally more accepted by players who are accustomed to failing an action based on the arbitrary roll of dice. This was probably more true of games in the 80s and early 90s than it is today. SaGa is among the first console RPGs, when games developers were still trying to figure out how these things should work. SaGa leans a bit more heavily into board games for inspiration than others at the time.

The influence of classic RPGs like Wizardry can be felt from the beginning of SaGa as well. The player must create an initial starting character, and after that new characters can be added and removed through a guild. In fact, the player is free to remove and create new party members as their evolving preferences or circumstances demands.

In SaGa’s case, character creation is a simple choice of the character’s race, which is a conflation of race and class seen in traditional RPGs. There are no other choices at character creation, stat allocation, or anything like that.

The mechanics of these three races is both the genius and source of ire for SaGa. They play wildly differently, such that a party of 2 humans and two espers is going to feel like a completely different game compared to 1 esper and 3 monsters. The key to appreciating SaGa is to recognize what you, the player, can control about your characters, what you cannot control, and how to manage the space in between.

Each race results is a completely different experience.

The differences in item slots is more important that may be obvious at first. Each character’s armor, weapons, and consumables all consume an item slot. This means if you want your esper to be fully armored, they might not have room for a weapon or a spell book. And you’ll need back-up weapons so each attack degrades a weapon’s durability until it breaks.

Outside of item capacity, the abilities of each race will dramatically change what you do with that character. Take espers, for example. Half of their precious 8 item slots are used for abilities that come and go throughout the game. These abilities change randomly (and without being announced after battle) so Fire (a group attack) may change into X Ice (weakness to ice) or Warning (prevent surprise attacks). If the player has an ability that they like, they either (1) check that they still have the ability after every fight and then save, reloading any time the ability is lost, or (2) accept the fact that the ability will randomly vanish at the roll of some ephemeral dice.

The unpredictable growth of espers is balanced by their special ability: using spell books that can wipe out groups of enemies and stats will raise naturally for free over time. These two qualities make mutants extremely powerful offensively, at the cost of less item slots. And if the mutant randomly gains a helpful natural ability, well that’s just a bonus.

Monsters are another area where players lament the lack of control and knowledge. When a monster eats meat after battle, they will transform into a new creature--which one exactly depends on what they are and what they eat. There’s a formula for figuring this out and the system can be gamed to access powerful monsters early, but it will feel largely random without a guide. Your monster could turn into something better; it could also turn into something weaker--you won’t know until you try.

The opaqueness of this system is offset by the advantages of exploring the system. Everytime a monster eats meat, its health is fully restored and it gains a full set of ability uses. If a monster is weakened and the player is away from an inn, eating meat can be a strategic choice to improve the longevity of the party since it refreshes the monster. Meat is provided frequently enough after battles, that players can really choose when to try their luck.

The system of transformations is also designed such that the more powerful the creature you are, the more powerful the creature you become. By the end of the game, the player will be able to turn into many powerful monsters and they will always turn into something equally awesome, regardless of how puny the foe they consume.

By recognizing that what monster you turn into or when and what abilities a mutant will acquire are not within the player’s control, and instead seeing the more opaque advantages each race has, the systems in SaGa are less mystery and more misunderstood. The player really needs to leave all expectations on how character development should work--including those learned in future entries in the series--to find any beauty.

God is Dead (Because We Killed Him)

While SaGa and Final Fantasy Legend are essentially the same game, there are some interesting differences in localization, branding, and reception.

For various reasons, video games appealed to a younger generation in North America than they did in Japan. For a game designed to appear to commuters in Japan to be marketed to the younger North American audience, some changes would be needed. Some modifications are obvious, like God as the penultimate villain was a non-starter for Nintendo of America. The artwork for SaGa was over the top in a way that would be wholly out of place on American store shelves, and would not benefit from the Final Fantasy name as intended.

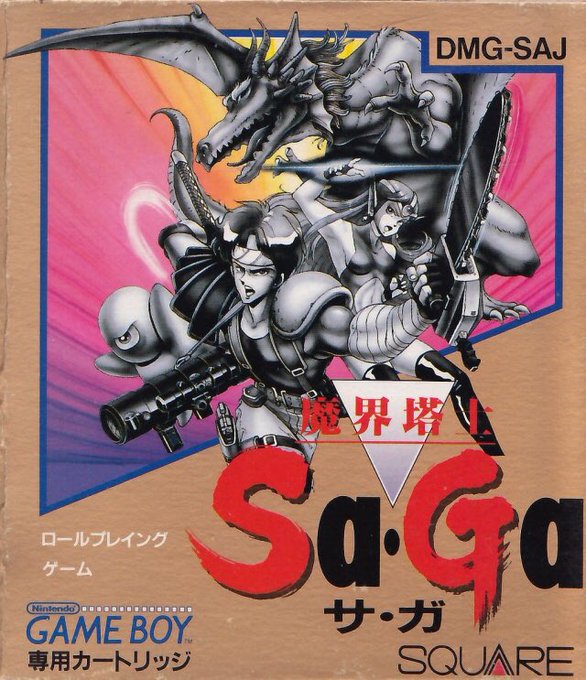

Just compare the artwork. SaGa’s cover is a dragon, mystic, and one-eyed blob monster behind a guy dual-wielding a chainsaw and a bazooka. Besides being phenomenally epic, it accurately conveys the mish-mash of fantasy and science fiction awesomeness that is SaGa. Compare this to the American box art, with a simple sword, helmet, and treasure illuminated by an elegant ray of light. They don’t even look like the same game. As was common for the era, the North American release also included a much thicker instruction manual with a walkthrough of the first few hours of the game, along with some hilariously bad 80s fantasy art.

The Japanese cover art (left) sets much more accurate expectations than the North American art (right).

Aside from the renaming of the final boss, much of SaGa is still here, albeit with some confusing localization choices. Many items have cryptic names (such as “shocker” curing paralysis), but there’s not a lot of these and many are explained in the manual. Several bosses are based on Chinese zodiac figures and these were left largely intact. A few wordy riddles were removed for the English localization, but that may have been due to space constraints (with English text requiring more bytes than Kanji). The smaller worlds are all the same, with the same events and enemies built around a central tower. All told, Final Fantasy Legend plays like SaGa, but with different branding.

There is one interesting localization change that does not appear to be censorship nor a text size constraint. Found near the end of the tower in Final Fantasy Legend, the player stumbles upon a library with messages that read “Ashura is controlled by…” with the final word being unreadable. This hint about the true villain doesn’t appear in SaGa. Instead, in Japanese, each book has a name, a number, and a date. Presumably these are the names of previous adventurers, the highest floor ascended in the tower, and the date of death. The last book has your first character’s name and a blank entry for the floor and date.

When you pause the game, the highest floor you’ve reached is listed. Maybe that’s not just for your information after all. It’s a dark bit of meta storytelling that’s kind of awesome.

New Life

I didn’t play a SaGa game until 2019. The prevailing wisdom of the Internet seemed to be that Final Fantasy Legend was weird, frustrating, and a bit unfun. Even here on HonestGamers, both staff reviews gave it a score of 1, and that’s not uncommon either.

Despite low expectations and no nostalgia for this title, I was shocked by just how much I enjoyed the experience. Once I understood and accepted what I could and could not control with my characters, I found a lot of enjoyment seeing them evolve, adapting to the situations the game threw at me, and trotting along through the game’s unique environments and story. When I was able to give up any preconceived notions of what an RPG should and should not do, SaGa turned into a fantastic and unique experience unlike any other RPG. Immediately after finishing it, I wanted to play again--not many RPGs have that kind of hold.

I’m not alone in feeling this way. SaGa turned out to be Square’s first game to sell over a million copies and did a lot to cement the company’s future as a pioneer in the RPG space. While other developers were content to mimic Dragon Quest, Square (and Kawazu in particular) were pushing the boundaries of what a game could do. SaGa is still one of the most important games of its era.

Despite its commercial success in Japan, Saga (and Japanese RPGs in general) still had an uphill battle to gain mainstream acceptance in the west. It wasn’t until the unabashed success of Final Fantasy VII and Pokemon Red and Blue that the localization floodgates opened. If you liked RPGs, the post-FFVII Playstation era was a golden age of getting games that just a few years earlier would have never been localized. The next game Square published after FFVII had the tide of goodwill and love from the newly claimed RPG market. That game was Saga Frontier. (Whoops)

SaGa Frontier was the first entry in that series to reach North America since Final Fantasy Legend III and the first to actually bear the SaGa name. It did not resonate well, being unfinished, having a borderline nonsensical localization, and cryptic gameplay that confused new RPG fans. It was at this time that SaGa got new life again thanks to its re-branding as Final Fantasy Legend. Sunsoft worked our a licensing agreement with Square to re-publish the original Final Fantasy Legend games to capitalize on the popularity of the Final Fantasy name. I can’t find clear sales figures, but anecdotally there are enough Sunsoft-branded copies of the three Legend games in the aftermarket to suggest that it was at least equally as successful as its initial print run that tried to capitalize on marketing for the original Final Fantasy.

During the years when Square’s relationship with Nintendo had fallen apart, SaGa received a fantastic remake on Bandi’s Wonderswan Color. It includes some quality of life features, such as seeing what monster you will transform into and better item descriptions. It also includes a decent adaptation of the original monochrome game for the purists. The fan translation is complete, and if you are lucky enough to have a Wonderswan or don’t mind playing through emulation, this is the version to play.

If you have a Switch, you can also pick up the Collection of SaGa. It’s a bit bare-bones but faithful enough to the original games, not to mention cheaper than what Final Fantasy Legend is selling for on the aftermarket these days.

If you do try it (or perhaps give it another chance), leave your expectations of what an RPG should be behind. Even today, the only games that are quite like SaGa are other SaGa games. It’s short duration, rapid battles, variety, fantastic setting, and unique mechanics all make it a worthy playthrough today just as much as it was in 1989. It’s aged wonderfully and even more than 30 years later, there’s still nothing quite like it.

|  |  |  |  |

Community review by dagoss (June 29, 2021)

A bio for this contributor is currently unavailable, but check back soon to see if that changes. If you are the author of this review, you can update your bio from the Settings page. |

|

More Reviews by dagoss [+]

|

|

If you enjoyed this The Final Fantasy Legend review, you're encouraged to discuss it with the author and with other members of the site's community. If you don't already have an HonestGamers account, you can sign up for one in a snap. Thank you for reading!

User Help | Contact | Ethics | Sponsor Guide | Links